Acclimatization and Altitude Sickness on Kilimanjaro

The altitude of Mount Kilimanjaro, African continent’s highest peak is 5,895 meters (19,341 feet). Kilimanjaro presents a unique set of challenges, the most dangerous of which being altitude sickness. A significant proportion of people who climb over 9,000ft develop some symptoms relating to altitude. At Climbing Kilimanjaro, Safety is our Number one priority.

Effects of Altitude on Kilimanjaro

Kilimanjaro has become a very popular trek as it’s a way for ordinary hikers to experience a high mountain summit with no technical skill. Being what’s known as a “walk-up”, without the need for ropes and climbing gear, some people underestimate the potential for serious, life-threatening situations as a result of the altitude.

Kilimanjaro’s summit falls into the “extreme altitude” category, along with Aconcagua and Denali (Mt McKinley). Everest and K2 are “ultra” altitude, where acclimatization is impossible.

A Brief Introduction to Altitude

At the summit of Kilimanjaro there is approximately 49% less oxygen than at sea level. However, it’s not the percentage of oxygen in the air that changes, it’s the barometric pressure (air pressure) of the atmosphere that’s reduced.

The percentage of oxygen in the air is the same 20.9%, but it’s availability is reduced by the reduction in air pressure. What this means, in simple terms is that for any volume of air you breathe in, there are less molecules of oxygen available.

The reduced air pressure has other problems associated with it as well, allowing fluid to collect outside of the cells, around the brain (High Altitude Cerebral Edema) and the lungs (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema), both very serious conditions.

Altitude Sickness: What is it?

Mountain sickness has three main forms: Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) and High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). Additionally, AMS can be mild (very common and manageable with the right treatment), moderate, and severe (immediate descent necessary).

Let’s take a closer look at these conditions.

Acute Mountain Sickness

According to Dr. Peter Hackett of the Institute for Altitude Medicine, AMS can affect anyone above 6,000ft. The initial sign is usually a headache, which confusingly can also be a sign of dehydration or over-exertion. If other symptoms develop, then a diagnosis of AMS is probable.

Mild AMS

In it’s mildest form, the symptoms can resemble that of a hangover, with nausea, headache, fatigue, and a loss of appetite. If you experience any of these symptoms it’s important to tell your guide and not simply try to push through. Mild symptoms can often be resolved with rest and adequate hydration.

Moderate AMS

If the symptoms of mild AMS start to get worse, a headache that you can’t shift, dizziness, coughing, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting this is an indication that you are not adapting to the altitude (acclimatizing) and at this point you should descend to the last elevation that you felt “well”.

Treatments such as ibuprofen for the headache or anti-emetics for the nausea can mask worsening symptoms and should not be relied upon for continued ascent.

Severe AMS

If a person suffering with moderate AMS ignores the symptoms pushing through to a higher elevation, there’s a risk that the condition can become severe. Severe AMS can lead to life-threatening complications (HAPE and HACE) and immediate descent is mandatory.

Symptoms can include severe headache, ataxia (lack of co-ordination, inability to walk properly, staggering), increased coughing and shortness of breath. Someone with severe AMS will likely need evacuation from the mountain either by stretcher or helicopter.

Complications resulting from severe mountain sickness are HAPE and HACE.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

Basecamp MD explains that HAPE can develop as a result of the lung arteries developing excessive pressure as a result of the low oxygen environment. This pressure causes build up of fluid around the lungs.

Confusingly, it’s possible for a climber to develop HAPE even if they don’t seem to have symptoms of severe AMS.

Look out for:

- Coughing up blood or mucus

- Abnormal lung sounds

- Extreme listlessness

- Difficulty breathing

- Lips going blue

- Confusion, lack of coordination

Anyone at altitude who feels as though they have a respiratory infection should assume it’s HAPE until a medical professional proves it to be otherwise. If HAPE is suspected, oxygen is often administered in conjunction with immediate evacuation to a medical facility.

As oxygen levels in the blood drop, the brain can suffer from lack of oxygen, leading to HACE.

High Altitude Cerebral Edema

HACE is a very dangerous condition that requires immediate medical treatment. As fluid builds up around the brain, the climber comes increasingly confused, lethargic and drowsy, incapable of walking and behaving strangely.

Look out for:

- Disorientation, confusion, hallucinations, talking nonsense

- Lack of coordination, staggering, inability to walk

- Irrational behavior

- Severe headache, sometimes accompanied by nausea and vomiting

HACE cannot be treated without immediate evacuation to a medical facility.

How is Altitude Sickness Diagnosed?

In our daily health checks, Climbing Kilimanjaro guides will use a pulse oximeter to measure your oxygen saturation and pulse rate and use this data along with any symptoms you are presenting to build up a picture of your situation.

Lake Louise Scoring System

Developed in 1991 and reviewed as recently as 2018, the Lake Louise Scoring System remains the basis for most diagnosis in the field of a climber’s condition. Climbing Kilimanjaro guides use this as a framework when they assess your condition. The ‘score’ attaches a number depending on the severity of your condition.

Headache

0—None at all

1—A mild headache

2—Moderate headache

3—Severe headache, incapacitating

Gastrointestinal symptoms

0—Good appetite

1—Poor appetite or nausea

2—Moderate nausea or vomiting

3—Severe nausea and vomiting, incapacitating

Fatigue and/or weakness

0—Not tired or weak

1—Mild fatigue/weakness

2—Moderate fatigue/weakness

3—Severe fatigue/weakness, incapacitating

Dizziness/light-headedness

0—No dizziness/light-headedness

1—Mild dizziness/light-headedness

2—Moderate dizziness/light-headedness

3—Severe dizziness/light-headedness, incapacitating

AMS Clinical Functional Score

Overall, if you had AMS symptoms, how did they affect your activities?

0—Not at all

1—Symptoms present, but did not force any change in activity or itinerary

2—My symptoms forced me to stop the ascent or to go down on my own power

3—Had to be evacuated to a lower altitude

[Source: High Altitude Medicine and Biology]

Acclimatization: Preventing Altitude Sickness

The term acclimatization or “acclimation” refers to the body’s compensatory processes to adapt to the low-oxygen, low-atmospheric pressure environment. From day one, your body will start to make adaptive changes to compensate.

Things you’ll notice:

- Breathing deeper, sometimes faster

- Elevated resting heart rate

- Potentially higher blood pressure.

As you ascend slowly, your body has certain mechanisms it uses to adapt:

- Producing more of the oxygen carrying hemoglobin

- Higher erythropoietin production, this is a hormone from the kidneys that increases the manufacture of red blood cells

- Lower volume of plasma, which can increase risk of dehydration.

- Higher kidney function as excess bicarbonate ions are excreted as a result of changing acid/alkali balance of blood.

All of these changes are a gradual process, which is why the best and safest summit success rates are had on routes with a good acclimatization protocol. The longer it takes to reach high altitude, the longer your body has to adapt.

By building in acclimatization days “hike high, sleep low” and rest days increases your chances of adequate adaptation, resulting in lower incidence of mountain sickness.

Acclimatization is a complicated process, some people seem to have no problem at all. There are no tricks or hacks, it’s a matter of time, although the medication Diamox has been shown to up regulate the body’s natural acclimatization processes and can help speed it up.

How to Avoid Altitude Sickness on Kilimanjaro

- Take a longer route. Instead of choosing the quickest way up Kilimanjaro, opt for a route that builds-in some acclimatization time. Also Kilimanjaro climb training and preparation is very important.

- Hike slowly. You’ll hear your guides reminding you of this “pole pole” (slowly, slowly in Swahili). You don’t want to tire yourself out, always try to be the last person into camp.

- Even if you’re very fit, you need to conserve your energy, avoid over-exertion. Fatigue is believed to be a major contributor to AMS.

- Stay hydrated. Keeping your fluids up prevents dehydration in the dry air which can compromise your ability to acclimatize

- Ask your doctor if Diamox is right for you.

- Don’t climb higher if you are suffering any symptoms of altitude sickness.

- Avoid narcotic pain killers, sleeping pills, alcohol or stimulants

- Always tell your guide if you have a headache, nausea or any other symptom

- Keep eating, particularly carbohydrates. The US Army studies show that carbohydrates increase ventilation, and are the most efficient fuel for high altitude exertion.

- Stay warm. Hypothermia is dangerous, never stay in wet clothes.

Does Altitude Training help Acclimatization?

Altitude Training is becoming increasingly popular among st would-be mountaineers. Some athletes use these training protocols to enhance performance, and studies have shown a “per-acclimatization” process as a result.

The protocols vary from training in a simulated altitude chamber, sleeping in a hypnotic tent, and even intermittent exposure to hypoxic air at rest. You can read our in depth guide to altitude training for more information.

The best pre-acclimatization method would be to climb Mt Meru, or some peaks in your home country prior to traveling to Kilimanjaro. This isn’t possible for everyone, nor is it necessary but if you do have access to some high altitude you’ll get a good idea of how well you acclimatize.

Effects of Altitude on existing Conditions

Your doctor will advise you of whether your medical history prevents you from traveling to altitude. Many people with well-controlled pre-existing conditions are able to climb Kilimanjaro successfully.

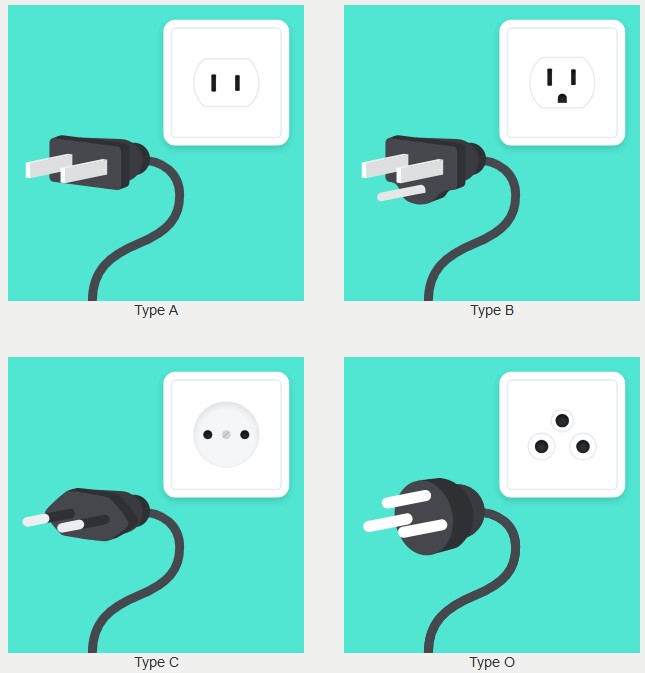

Anyone with heart, lung or neurological conditions will need to have a medical sign-off from their doctor before joining one of our climbs. It’s particularly important for your doctor to assess how the altitude may affect your current medications and condition. Be aware that certain medical conditions may make getting adequate travel insurance more difficult.

Effects of Altitude on Sleep: Cheyne-Stokes Breathing

One of the main reasons for sleep disturbance at altitude is periodic breathing. This is not necessarily associated with altitude sickness, but can be uncomfortable and disruptive. The Institute for Altitude Medicine explains that it’s a “battle in the body over control of breathing during sleep”. The oxygen sensors tell the parasympathetic nervous system to breathe more deeply, whilst the carbon dioxide sensors tell it to stop.

The result is usually deep breathing followed by the breathing stopping, and then a deep-breath as it restarts. Diamox often helps with this condition.

Other Health Considerations on Kilimanjaro

While altitude sickness is the main concern, you need to take a pro-active view of your health whilst climbing.

Hypothermia

Never stay in wet clothes. Whether from rainfall or perspiration, once you stop moving, a slight chill can turn to hypothermia in a short time, especially higher up the mountain. Make sure you carry adequate layers in your day pack, as rapid changes in temperature are quite common as you ascend.

The Sun’s Rays

Always wear sunscreen, preferably factor 40+, cover exposed parts of your body, including your head and neck. As you ascend, there is less atmosphere to filter out the harmful UV rays, and the sun’s rays are harsh.

Most importantly, wear sunglasses that block 100% of the UV rays. Wraparound glasses are best, to prevent reflected UV off glaciers and snow from damaging your eyes. Snow blindness is not common, but it’s a definite risk if you don’t protect your eyes.

Gastro-intestinal issues

Any travel to remote places comes with a risk of gastro-intestinal trouble. Different foods, sub-standard hygiene, and exposure to bacteria and viruses can cause stomach problems. Always use anti-bacterial gel or wipes on your hands, especially before eating.

Your main risk for stomach trouble is before your climb. Avoid eating at street stalls, stay away from tap water, salads, and fruit you can’t peel. On the mountain we adhere to strict food hygiene protocols and provide safe purified water at all times.

Climbing Kilimanjaro Safety Procedures

At climbing Kilimanjaro we take your safety very seriously. Climbing Kilimanjaro trained guides will monitor you closely, but to do that, they also need your help. If you feel in any way unwell, you should inform your guide immediately. Keep an eye on other members of your group, if you see someone behaving strangely or they appear to be suffering, tell your guide.

Every day your guide will check your oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter, question you about how you are feeling, and listen to your chest for unusual lung sounds. Catching it early is the best way to prevent mild altitude sickness escalating.

Climbing Kilimanjaro Team carries emergency oxygen and there are portable stretcher provided by the National Park on every climb. If a climber is suffering and cannot proceed, we have partnered with Kilimanjaro helicopter rescue for emergency evacuation.